When I meet a new client who has recently been arrested one of the first things that I am often told is, “they never read me my rights!” My follow-up question to this statement is whether the police questioned that client. If the answer is “no” then the police were under no obligation to inform that person of his “Miranda rights.” I understand why so many of my clients assume that they were supposed to have been informed of these rights at the time of arrest. On cop shows like Law and Order, the police always tell the person of his right to remain silent as soon as the cuffs go on and the remaining warnings are recited as the accused is led to the police car. It makes for great TV, but that is not required under federal law nor under the laws of any state of which I am aware.

When I meet a new client who has recently been arrested one of the first things that I am often told is, “they never read me my rights!” My follow-up question to this statement is whether the police questioned that client. If the answer is “no” then the police were under no obligation to inform that person of his “Miranda rights.” I understand why so many of my clients assume that they were supposed to have been informed of these rights at the time of arrest. On cop shows like Law and Order, the police always tell the person of his right to remain silent as soon as the cuffs go on and the remaining warnings are recited as the accused is led to the police car. It makes for great TV, but that is not required under federal law nor under the laws of any state of which I am aware.

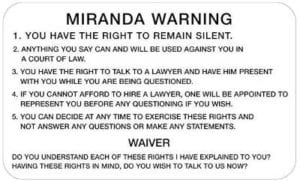

To the credit of TV police show (which generally lack educational value), many people who have never been arrested or otherwise subject to criminal investigation have a basic understanding of “Miranda rights.” As is required by the US Supreme Court in Miranda v. Arizona, a person subject to interrogation by police while in custody must be told of his/her: (1) right to remain silent; (2) that anything said can be used against him/her in court; (3) right to consult with an attorney before speaking to the police and to have an attorney present during questioning; (4) that an attorney will be provided if s/he cannot afford one; (5) that if s/he decides to answer questions, s/he can stop answering at any time.

Only after a person in custody is informed of these rights and waives these rights can the interrogation proceed. If this requirement is not strictly followed, any statement made by the accused while in custody in response to police questioning can be suppressed (which means that the statement cannot be presented as evidence at trial.)

Under Massachusetts state law there is also the “humane practice” rule. Under that rule, even where Miranda rights were properly given and waived, or in situations where the warnings were not required (such as where the person is not in custody or not subject to police interrogation), the statements can still be suppressed if they are not voluntary. The court will consider factors such as the defendant’s age, education, intelligence, emotional stability, physical or mental conditions, and experience with the criminal justice system in determining voluntariness.

In a recent case in the Middlesex Superior Court, I convinced a judge to suppress my client’s confession to a masked armed robbery for both Miranda violations and voluntariness. The judge found that the detective who questioned my client failed to advise him of his right to consult with an attorney. The judge also found, following the testimony of a psychologist who I hired on the same day that I met my client following his arrest, that my client’s mental illness was so pronounced at the time of questioning that his statement was not voluntary. Once his confession was suppressed, the government did not have enough evidence to proceed with the charges against my client and the case was dismissed.

Miranda warnings are an important protection for people accused of crime, but only those who are in custody and are questioned about the crime by police. Miranda warnings are not required for people who are not in custody or who are not being directly questioned about the crime. If a person volunteers information without being questioned about a crime, that statement cannot be suppressed for a Miranda violation (but can be suppressed under voluntariness grounds in the Massachusetts state courts.)

If you are questioned by police about your involvement in a crime, I encourage you to refuse to answer questions and consult with an attorney before answering questions even if you believe that you have nothing to hide. If you have anything to say that you think ought to be shared with law enforcement, please contact me so that we can talk about it privately and calmly. If after discussing the issue, we feel that it ought to be shared, we can arrange to speak to the prosecutor or detective together.