As I write this, there is a COVID-19 outbreak that is claiming lives and overwhelming our healthcare system. My state, Massachusetts, was one of the earlier states to be hit hard with a COVID-19 outbreak via community transmission. The Governor declared a State of Emergency, prohibited gatherings of over 25 people, closed schools, ordered all bars and restaurants to suspend on-site gatherings, and encourage everyone to shelter in place. The U.S. District Court and Massachusetts Trial Courts responded by delaying all jury trials. The Massachusetts Trial Courts have taken a further step and continued most cases where the accused is not in custody for several weeks while conducting hearings for people in custody via telephone conference. The U.S. District Court is conducting hearings via video conferencing to minimize people coming in and of the courthouse.

The prevailing issue right now for criminal defense attorneys is to get people who are in custody released, particularly those who are elderly and/or have preexisting conditions that put them at heightened risk of death should they contract the virus. As COVID-19 spreads in our communities it is of no surprise that it is also spreading in our jails and prisons. There, people live by design in uncomfortably close quarters and social distancing is impossible. While jails and prisons have suspended visitors and volunteers from entering the facilities, staff still need to report for work and deliveries still need to be made. I have been tracking confirmed cases of coronavirus in jails and prisons throughout the country and as I write there are hundreds of cases of people in custody and jail staff who have been afflicted. The most alarming is Rikers Island where, as of April 5, 2020, there are 273 inmates and 374 staff members who have the virus. This gives Rikers the distinction of the highest infection rate per capita in the entire world. To date, 1 inmate and 4 staff members from Rikers have died from COVID. In Massachusetts I am aware of 39 confirmed COVID cases among prisoners at various facilities and 27 staff members. The most alarming is MTC in Bridgewater, a state facility where 23 inmates have contracted the virus and three have died as of April 4, 2020. The body count is rising; as of April 5, 2020, I am aware of the deaths of 5 inmates at FCI Oakdale, 3 inmates at FCI Elkton, 1 inmate and 1 corrections officer from the Michigan state prison system, 1 inmate from New York’s Sing Sing facility, 1 corrections officer at Wayne County Jail in Detroit, 1 inmate from Illinois Department of Corrections, 1 inmate from a Georgia state prison, 2 jail staff working for the Riverside County Sheriffs in California, and 1 corrections officer with the D.C. Department of Youth Services.

The argument against releasing people from custody is that they may present a danger to the community which is why they were locked up in the first place. If you think that the only people in jails and prisons are pathologically dangerous and gunning to wreak havoc upon release, you’ve been watching too many episodes of Oz. There are all types of people in jails and prisons, many of whom would not pose a risk to the community if released. The greater danger is to keep detention facilities at their present capacity; releasing prisoners who pose little risk to the community reduces the density of inmate population and slows the transmission of the virus which will enter every facility in this country eventually. People who contract the virus need urgent medical care and detention facilities do not have the capacity to treat the sick and to contain the spread of the virus. The sickest inmates will be transferred to local hospitals and will overwhelm the healthcare system, particularly in rural areas. Conditions that favor COVID transmission hurt staff members too. On Thursday March 19, the Chief Medical Officer for the New York City Jails, Ross MacDonald, wrote on Twitter:

We will put ourselves at personal risk and ask little in return. But we cannot change the fundamental nature of jail. We cannot socially distance dozens of elderly men living in a dorm, sharing a bathroom. Think of a cruise ship recklessly boarding more passengers each day. A storm is coming and I know what I’ll be doing when it claims my first patient. What will you be doing? What will you have done? We have told you who is at risk. Please let as many out as you possibly can. end.

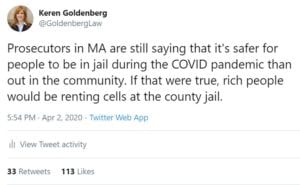

I have had some success with these motions for release so far. I prepared a list of confirmed COVID cases in jails and prisons that I use as as an exhibit to my motion for release to demonstrate how dire the situation is and have kept it updated and shared it with other lawyers trying to get their clients out. Many prosecutors are fiercely opposing release despite the obvious dangers of retaining the status quo. Prosecutors point out that jail and prison facilities have forbidden visitors and some have even put inmates on lockdown so that they can’t leave their cells or dorms. These policy changes in response to the COVID outbreak are insufficient since staff continue to enter and exit the facilities, deliveries continue to be made, and the number of confirmed cases has kept rising. Also, given that conditions of confinement have gotten dramatically worse for inmates who have not had disciplinary problems, shouldn’t that lend favor to their release? But the most insulting argument of all is the claim that our clients are actually safer locked up in detention facilities rather than in their homes. This incorrectly assumes that all detained people have nowhere stable to go and that they will not abide by stay at home orders issued by local and state officials. Many people in custody have family and friends who love them, are worried about them, and want them to come home. Leaving them in crowded detention facilities where they are at greater risk of exposure to a potentially fatal virus is nothing short of cruel and suggesting that it’s for their own good is maddening. Judges are making their rulings on these motions slowly when quick decisions are essential.

Recognizing that individual lawyers filing motions for the release of each of their clients does not adequately address the urgency of the present situation, the Committee for Public Counsel Services, ACLU of Massachusetts, and the Massachusetts Association of Defense Attorneys filed an emergency petition asking the Supreme Judicial Court to take immediate action to limit the spread of COVID-19 by reducing the number of people who are incarcerated in Massachusetts jails and prisons. The petition asked the Court to limit the number of people taken into custody, reduce the number of people held pretrial, and release some people serving sentences who are vulnerable to COVID-19 or near the end of their sentences.

Despite fantastic efforts by the lawyers who brought this petition, the Court’s ruling was mediocre at best and inadequate to address this desperate situation. Positive developments are that the Court ruled that people who are held pre-trial on bail who are not charged with a violent or otherwise excluded offense are entitled to a hearing withing two business days of filing their motions and that there would be a rebuttable presumption of their release. Unfortunately the list of excluded offense (meaning that people charged with those crimes would not be granted this consideration) is quite expansive. Also unfortunate is that the Court did not offer new and quicker avenues of relief for people serving sentences. They ruled that people can move to stay (delay) their sentences while their appeals are being litigated but otherwise need to rely on traditional avenues of relief. Given that MTC (the facility where three people have died) only holds people serving sentences, many of whom are beyond the appellate stage, relief for people trapped inside will be slow and sparing.

I leave you with wise words from Matt Segal, one of the ACLU lawyers involved in the emergency petition: